REVIEW

SA JOURNAL OF DIABETES & VASCULAR DISEASE

64

VOLUME 12 NUMBER 2 • NOVEMBER 2015

subjects with diabetes (SES 614 and BMS 645) were included, with

an average age of 65 years. The sample sizes ranged from 83 to

458, and the studies were RCTs and non-RCTs.

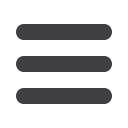

The efficacy of SES versus BMS is presented in Table 2. As shown,

the pooled OR was 0.42 (95% CI: 0.24–0.74,

p

< 0.01) for SES

versus BMS. This suggests that, after the data had been pooled,

SES were more effective than BMS in CAD patients with diabetes.

However, there was publication bias (

t

= –4.19,

p

< 0.05).

As shown in Fig. 2A, the pooled OR was 0.42 (95% CI: 0.24–

0.74,

p

< 0.01) for overall events, suggesting that SES had a better

outcome compared with BMS, with a greater reduction in risk for

major cardiac events. However, there were heterogeneities between

the studies (

Q

2

= 20.14,

I

2

= 75.0%,

p

< 0.1) and publication bias,

as shown in Fig. 2B (asymmetric funnel plot). This was further

confirmed with Egger’s linear regression test, shown in Table 2 (

t

= –4.19,

p

< 0.05).

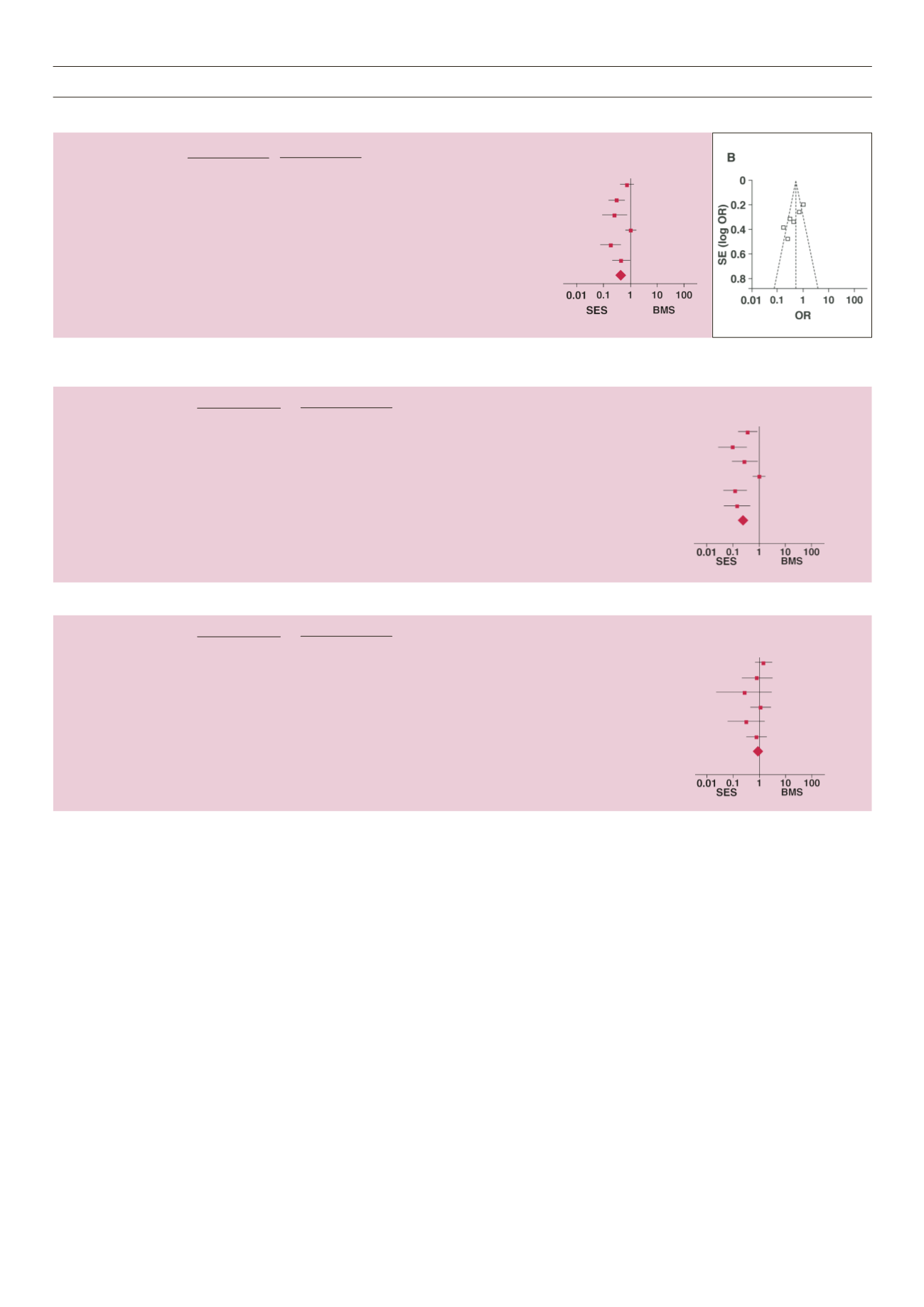

As shown in Fig. 3, the pooled OR was 0.26 (95% CI: 0.11–0.59,

p

< 0.01) for SES versus BMS, suggesting that SES had a better

revascularisation rate for target lesions comparedwith BMS. However,

there were heterogeneities between the studies (

Q

2

= 24.44,

I

2

=

80.0%,

p

< 0.1) and publication bias (

t

= –6.44, p < 0.05).

As shown in Fig. 4, the pooled OR was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.61–

1.40,

p

> 0.05) for SES versus BMS, suggesting that the overall risk

for myocardial infarction was not significantly different between

these two groups. There was no heterogeneity between the studies

(

Q

2

= 4.37,

I

2

= 0%,

p

> 0.1) but there was publication bias (

t

=

–3.44,

p

< 0.05).

As shown in Fig. 5, the pooled OR was 1.19 (95% CI: 0.74–1.92,

p

> 0.05) for SES versus BMS, suggesting that the overall risk of

mortality was not significantly different between the groups. There

was no publication bias (

t

= –1.69,

P

> 0.05) or heterogeneities

between the studies (

Q

2

= 3.88,

I

2

= 0.0%,

p

> 0.1).

Subgroup analyses were stratified by sample size, subjects’

geographical area and study method. As shown in Table 2 and

Figure 6A–C, the pooled OR was 0.28 (95% CI: 0.16–0.48,

p

<

0.01, Fig. 6A) for SES versus BMS in studies whose sample size was

A

SES

BMS

Odds ratio

Odds ratio

Study or subgroup

Events Total Events Total Weight (%) M–H, random, (95% CI) M–H, random, (95% CI)

Aoki J,

et al.

27

112

37

118

18.5

0.70 (0.39–1.24)

Baumgart D,

et al.

15

94

38

96

17.2

0.29 (0.15–0.58)

Chan C,

et al.

8

54

12

29

12.8

0.25 (0.09–0.71)

Daemen J,

et al.

44

206

54

252

20.1

1.00 (0.64–1.56)

Jimenez-Quevedo P,

et al.

8

80

31

80

15.0

0.18 (0.07–0.41)

Maresta A,

et al.

15

68

28

70

16.4

0.42 (0.20–0.90)

Total (95% CI) 614 645

100.0

0.42 (0.24–0.74)

Total events

117

200

Heterogeneity: Tau

2

= 0.36; Chi

2

= 20.14, df = 5 (

p

= 0.001); I2 = 75%

Test for overall effect: Z = 3.00 (

p

= 0.003)

SES

BMS

Odds ratio

Odds ratio

Study or subgroup

Events

Total

Events

Total

Weight (%)

M–H, random, (95% CI)

M–H, random, (95% CI)

Aoki J,

et al

.

9

112

23

118

17.9

0.36 (0.16–0.82)

Baumgart D,

et al

3

94

24

96

14.6

0.10 (0.03–0.34)

Chan C,

et al

.

7

54

10

29

15.7

0.28 (0.09–0.85)

Daemen J,

et al

.

28

206

35

252

19.9

0.98 (0.57–1.67)

Jimenez-Quevedo P,

et al

5

80

28

80

16.4

0.12 (0.04–0.34)

Maresta A,

et al

.

4

68

21

70

15.5

0.15 (0.05–0.45)

Total (95% CI) 614 645

100.0

0.26 (0.11–0.59)

Total events

56

141

Heterogeneity: Tau

2

= 0.83; Chi

2

= 24.44, df = 5 (

p

= 0.0002);

I

2

= 80%

Test for overall effect: Z = 3.22 (

p

= 0.001)

SES

BMS

Odds ratio

Odds ratio

Study or subgroup

Events

Total

Events

Total

Weight (%)

M–H, random, (95% CI)

M–H, random, (95% CI)

Aoki J,

et al

.

18

112

14

118

25.1

1.42 (0.67–3.02)

Baumgart D, et al.

4

94

5

96

10.4

0.81 (0.21–3.11)

Chan C,

et al

.

1

54

2

29

5.6

0.25 (0.02–2.94)

Daemen J,

et al

.

10

206

11

252

20.7

1.12 (0.47–2.69)

Jimenez-Quevedo P,

et al

.

2

80

6

80

12.8

0.32 (0.06–1.62)

Maresta A,

et al

.

11

68

14

70

25.4

0.77 (0.32–1.85)

Total (95% CI) 614 645

100.0

0.92 (0.61–1.40)

Total events

46

52

Heterogeneity: Chi

2

= 4.37, df = 5 (

p

= 0.50);

I

2

= 0%

Test for overall effect: Z = 0.37 (

p

= 0.71)

Figure 2

. A: Forest plots of studies with major adverse cardiac events in the SES group versus the BMS group. B: Funnel plots of studies with major adverse cardiac

events in the SES group versus the BMS group.

Figure 3

. Forest plots of studies with target-lesion revascularisation events in the SES group versus the BMS group.

Figure 4

. Forest plots of studies with myocardial infarction events in the SES group versus the BMS group.